W. E. Watt, President &c.,

Fisher Building,

277 Dearborn St., Chicago, Ill.

My dear Sir:

Please accept my thanks for a copy of the first publication of “Birds.” Please enter my name as a regular subscriber. It is one of the most beautiful and interesting publications yet attempted in this direction. It has other attractions in addition to its beauty, and it must win its way to popular favor.

Wishing the handsome little magazine abundant prosperity, I remain

Yours very respectfully,

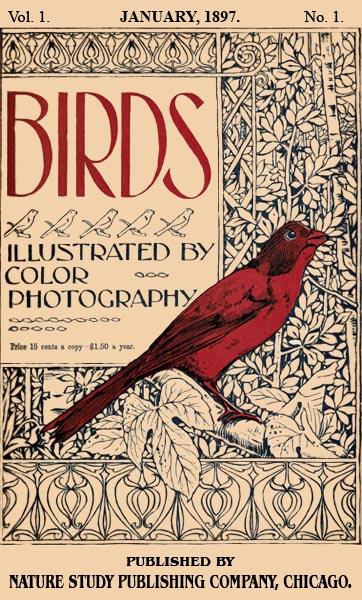

Vol. 1. No. 1. JANUARY, 1897. PRICE 15 CENTS: $1.50 A YEAR.

ONCE A MONTH.

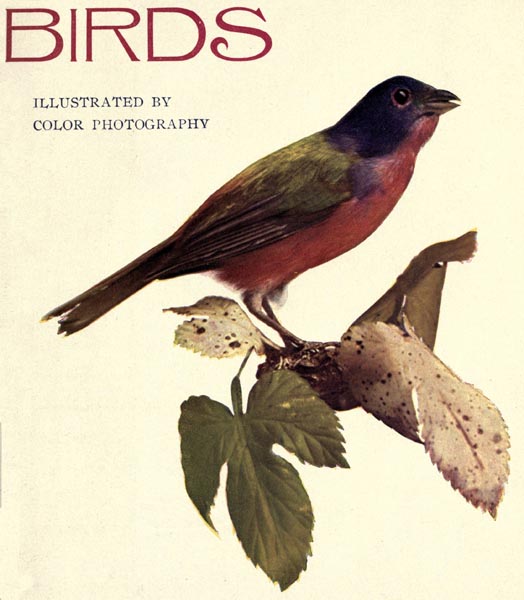

nonpareil.

nonpareil.

Nature Study Publishing Company

OFFICE: FISHER BUILDING

CHICAGO

BIRDS

ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY

A MONTHLY SERIAL

DESIGNED TO PROMOTE

KNOWLEDGE OF BIRD-LIFE

“With cheerful hop from perch to spray,

They sport along the meads;

In social bliss together stray,

Where love or fancy leads.

Through spring’s gay scenes each happy pair

Their fluttering joys pursue;

Its various charms and produce share,

Forever kind and true.”

CHICAGO, U. S. A.

Nature Study Publishing Company, Publishers

1896

PREFACE.

T has become a universal custom to obtain and preserve the likenesses of one’s friends. Photographs are the most popular form of these likenesses, as they give the true exterior outlines and appearance, (except coloring) of the subjects. But how much more popular and useful does photography become, when it can be used as a means of securing plates from which to print photographs in a regular printing press, and, what is more astonishing and delightful, to produce the real colors of nature as shown in the subject, no matter how brilliant or varied.

We quote from the December number of the Ladies’ Home Journal: “An excellent suggestion was recently made by the Department of Agriculture at Washington that the public schools of the country shall have a new holiday, to be known as Bird Day. Three cities have already adopted the suggestion, and it is likely that others will quickly follow. Of course, Bird Day will differ from its successful predecessor, Arbor Day. We can plant trees but not birds. It is suggested that Bird Day take the form of bird exhibitions, of bird exercises, of bird studies—any form of entertainment, in fact, which will bring children closer to their little brethren of the air, and in more intelligent sympathy with their life and ways. There is a wonderful story in bird life, and but few of our children know it. Few of our elders do, for that matter. A whole day of a year can well and profitably be given over to the birds. Than such study, nothing can be more interesting. The cultivation of an intimate acquaintanceship with our feathered friends is a source of genuine pleasure. We are under greater obligations to the birds than we dream of. Without them the world would be more barren than we imagine. Consequently, we have some duties which we owe them. What these duties are only a few of us know or have ever taken the trouble to find out. Our children should not be allowed to grow to maturity without this knowledge. The more they know of the birds the better men and women they will be. We can hardly encourage such studies too much.”

Of all animated nature, birds are the most beautiful in coloring, most graceful in form and action, swiftest in motion and most perfect emblems of freedom.

They are withal, very intelligent and have many remarkable traits, so that their habits and characteristics make a delightful study for all lovers of nature. In view of the facts, we feel that we are doing a useful work for the young, and one that will be appreciated by progressive parents, in placing within the easy possession of children in the homes these beautiful photographs of birds.

The text is prepared with the view of giving the children as clear an idea as possible, of haunts, habits, characteristics and such other information as will lead them to love the birds and delight in their study and acquaintance.

NATURE STUDY PUBLISHING CO.

Copyrighted, 1896.

nonpareil.

nonpareil.

THE NONPAREIL.

I am called the Nonpareil because there is no other bird equal to me.

I have many names. Some call me the “Painted Finch” or “Painted Bunting.” Others call me “The Pope,” because I wear a purple hood.

I live in a cage, eat seeds, and am very fond of flies and spiders.

Sometimes they let me out of the cage and I fly about the room and catch flies. I like to catch them while they are flying.

When I am tired I stop and sing. There is a vase of flowers in front of the mirror.

I fly to this vase where I can see myself in the glass. Then I sing as loud as I can. They like to hear me sing.

I take a bath every day and how I do make the water fly!

I used to live in the woods where there were many birds like me. We built our nests in bushes, hedges, and low trees. How happy we were.

My cage is pretty but I wish I could go back to my home in the woods.

See page 15.

WEET warblers of the sunny hours,

WEET warblers of the sunny hours,

Forever on the wing,

I love thee as I love the flowers,

The sunlight and the spring.

They come like pleasant memories

In summer’s joyous time,

And sing their gushing melodies,

As I would sing a rhyme.

In the green and quiet places,

Where the golden sunlight falls,

We sit with smiling faces

To list their silver calls.

And when their holy anthems

Come pealing through the air,

Our hearts leap forth to meet them

With a blessing and a prayer.

Amid the morning’s fragrant dew,

Amid the mists of even,

They warble on as if they drew

Their music down from heaven.

How sweetly sounds each mellow note

Beneath the moon’s pale ray,

When dying zephyrs rise and float

Like lovers’ sighs away!”

THE RESPLENDENT TROGON.

A Letter to Little Boys and Girls of the United States.

Is it cold where you live, little boys and girls? It is not where I live. Don’t you think my feathers grew in the bright sunshine?

My home is way down where the big oceans almost meet. The sun is almost straight overhead every noon.

I live in the woods, way back where the trees are tall and thick. I don’t fly around much, but sit on a limb of a tree way up high.

Don’t you think my red breast looks pretty among the green leaves?

When I see a fly or a berry I dart down after it. My long tail streams out behind like four ribbons. I wish you could see me. My tail never gets in the way.

Wouldn’t you like to have me sit on your shoulder, little boy? You see my tail would reach almost to the ground.

If you went out into the street with me on your shoulder, I would call whe-oo, whe-oo, the way I do in the woods.

All the little boys and girls playing near would look around and say, “What is that noise?” Then they would see you and me and run up fast and say, “Where did you get that bird?”

The little girls would want to pull out my tail feathers to put around their hats. You would not let them, would you?

I have a mate. I think she is very nice. Her tail is not so long as mine. Would you like to see her too? She lays eggs every year, and sits on them till little birds hatch out. They are just like us, but they have to grow and get dressed in the pretty feathers like ours. They look like little dumplings when they come out of the eggs.

But they are all right. They get very hungry and we carry them lots of things to eat, so they can grow fast.

Your friend,

R. T.

resplendent trogon.

resplendent trogon.

THE RESPLENDENT TROGON.

ESPLENDENT Trogons are natives of Central America. There are fifty kinds, and this is the largest. A systematic account of the superb tribe has been given by Mr. Gould, the only naturalist who has made himself fully acquainted with them.

Of all birds there are few which excite so much admiration as the Resplendent Trogon.

The skin is so singularly thin that it has been not inaptly compared to wet blotting paper, and the plumage has so light a hold upon the skin that when the bird is shot the feathers are plentifully struck from their sockets by its fall and the blows which it receives from the branches as it comes to the ground.

Its eggs, of a pale bluish-green, were first procured by Mr. Robert Owen. Its chief home is in the mountains near Coban in Vera Paz, but it also inhabits forests in other parts of Guatemala at an elevation of from 6,000 to 9,000 feet.

From Mr. Salvin’s account of his shooting in Vera Paz we extract the following hunting story:

“My companions are ahead and Filipe comes back to say that they have heard a quesal (Resplendent Trogon). Of course, being anxious to watch as well as to shoot one of these birds myself, I immediately hurry to the spot. I have not to wait long. A distant clattering noise indicates that the bird is on the wing. He settles—a splendid male—on the bough of a tree not seventy yards from where we are hidden. It sits almost motionless on its perch, the body remaining in the same position, the head only moving from side to side. The tail does not hang quite perpendicularly, the angle between the true tail and the vertical being perhaps as much as fifteen or twenty degrees. The tail is occasionally jerked open and closed again, and now and then slightly raised, causing the long tail coverts to vibrate gracefully. I have not seen all. A ripe fruit catches the quesal’s eye and he darts from his perch, plucks the berry, and returns to his former position. This is done with a degree of elegance that defies description. A low whistle from Capriano calls the bird near, and a moment afterward it is in my hand—the first quesal I have seen and shot.”

The above anecdote is very beautiful and graphic, but we read the last sentence with pain. We wish to go on record with this our first number as being unreconciled to the ruthless killing of the birds. He who said, not a sparrow “shall fall on the ground without your Father,” did not intend such birds to be killed, but to beautify the earth.

The cries of the quesal are various. They consist principally of a low note, whe-oo, whe-oo, which the bird repeats, whistling it softly at first, then gradually swelling it into a loud and not unmelodious cry. This is often succeeded by a long note, which begins low and after swelling dies away as it began. Other cries are harsh and discordant. The flight of the Trogon is rapid and straight. The long tail feathers, which never seem to be in the way, stream after him. The bird is never found except in forests of the loftiest trees, the lower branches of which, being high above the ground, seem to be its favorite resort. Its food consists principally of fruit, but occasionally a caterpillar is found in its stomach.

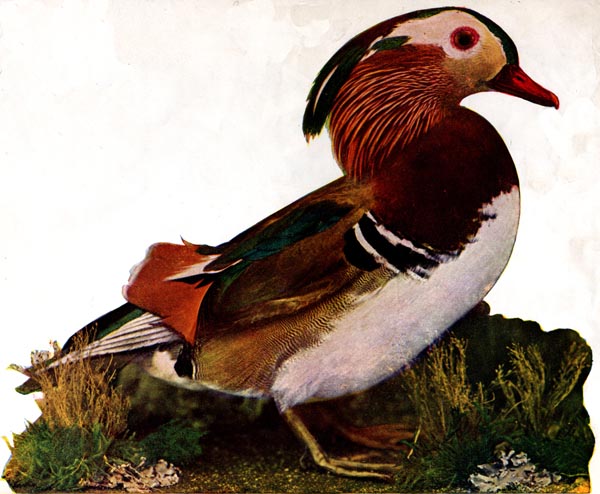

THE MANDARIN DUCK.

A Letter from China.

Quack! Quack! I got in just in time.

I came as fast as I could, as I was afraid of being whipped. You see I live in a boat with a great many other ducks.

My master and his family live in the boat too. Isn’t that a funny place to live in?

We stay in all night. Waking up early in the morning, we cry Quack! Quack! until we wake the master.

He gets up and opens the gate for us and out we tumble into the water. We are in such a hurry that we fall over each other. We swim about awhile and then we go to shore for breakfast.

There are wet places near the shore where we find worms, grubs, and roots. When evening comes the master blows a whistle. Then we know it is time to come home.

We start as soon as we hear it, and hurry, because the last duck in gets a whipping. It does not hurt much but we do not like it, so we all try to get home first.

I have web feet, but I perch like other birds on the branches of the trees near the river.

My feathers are beautiful in the sunlight. My wife always sits near me. Her dress is not like mine. It is brown and grey.

From May to August I lose my bright feathers, then I put on a dress like my wife’s.

My master’s family are Chinese, and they are very queer. They would not sell me for anything, as they would not like to have me leave China.

Sometimes a pair of us are put in a gay cage and carried to a wedding. After the wedding we are given to the bride and groom.

I hear the master’s whistle again. He wants me to come in and go to bed. Quack! Quack! Good bye!

mandarin duck.

mandarin duck.

THE MANDARIN DUCK.

MORE magnificently clothed bird,” says Wood, “than the male Chinese Mandarin Duck, can hardly be found, when in health and full nuptial plumage. They are natives of China and Japan, and are held in such high esteem by the Chinese that they can hardly be obtained at any price, the natives having a singular dislike to seeing the birds pass into the possession of Europeans.”

Though web-footed, the birds have the power of perching and it is a curious sight to watch them on the branches of trees overhanging the pond in which they live, the male and female being always close together, the one gorgeous in purple, green, white, and chestnut, and the other soberly appareled in brown and grey. This handsome plumage the male loses during four months of the year, from May to August, when he throws off his fine crest, his wing-fans, and all his brilliant colors, assuming the sober tinted dress of his mate. The Summer Duck of America bears a close resemblance to the Mandarin Duck, both in plumage and manners, and at certain times of the year is hardly to be distinguished from that bird.

The foreign duck has been successfully reared in Zoological Gardens, some being hatched under the parent bird and others under a domestic hen, the latter hatching the eggs three days in advance of the former.

“The Chinese,” says Dr. Bennett, “highly esteem the Mandarin Duck, which exhibits, as they think, a most striking example of conjugal attachment and fidelity. A pair of them are frequently placed in a gaily decorated cage and carried in their marriage processions, to be presented to the bride and groom as worthy objects of emulation.”

“I could more easily,” wrote a friend of Dr. Bennett’s in China to whom he had expressed his desire for a pair of these birds, “send you two live Mandarins than a pair of Mandarin Ducks.”

Concerning their attachment and fidelity to one another, Dr. Bennett recites the following:

“Mr. Beale’s aviary at Maceo one day was broken open and the male bird stolen from the side of its mate. She refused to be comforted, and, retiring to the farthest part of the aviary, sat disconsolate, rarely partaking of food, and giving no attention to her soiled and rumpled plumage. In vain did another handsome drake endeavor to console her for her loss. After some time the stolen bird was found in the quarters of a miserable Chinaman, and at once restored to its mate. As soon as he recognized his abode he began to flap his wings and quack vehemently. She heard his voice and almost quacked to screaming with ecstasy, both expressing their joy by crossing necks and quacking in concert. The next morning he fell upon the unfortunate drake who had made consolatory advances to his mate, pecked out his eyes and so injured him that the poor fellow died in the course of a few days.”

According to Schrenck, this species appears in the countries watered by the Amoor about May, and departs again at the end of August; at this season it is always met with in small or large flocks, which are so extremely shy that they rarely come within gunshot. Whilst on the wing these parties crowd closely together in front, the birds in the rear occupying a comparatively free space.

THE GOLDEN PHEASANT

They call me the Golden Pheasant, because I have a golden crest. It is like a king’s crown. Don’t you think my dress is beautiful enough for a king?

See the large ruff around my neck. I can raise and lower it as I please.

I am a very large bird. I am fourteen inches tall and twenty-eight inches long. I can step right over your little robins and meadow larks and blue jays and not touch them.

Sometimes people get some of our eggs and put them under an old hen. By and by little pheasants hatch out, and the hen is very good to them. She watches over them and feeds them, but they do not wish to stay with her; they like their wild life. If they are not well fed they will fly away.

I have a wife. Her feathers are beginning to grow like mine. In a few years she will look as I do. We like to have our nests by a fallen tree.

HE well-known Chinese Pheasant, which we have named the Golden Pheasant, as well as its more sober-colored cousin, the Silver Pheasant, has its home in Eastern Asia.

China is pre-eminently the land of Pheasants; for, besides those just mentioned, several other species of the same family are found there. Japan comes next to China as a pheasant country and there are some in India.

In China the Golden Pheasant is a great favorite, not only for its splendid plumage and elegant form, but for the excellence of its flesh, which is said to surpass even that of the common pheasant. It has been introduced into Europe, but is fitted only for the aviary.

For purposes of the table it is not likely to come into general use, as there are great difficulties in the way of breeding it in sufficient numbers, and one feels a natural repugnance to the killing of so beautiful a bird for the sake of eating it. The magnificent colors belong only to the male, the female being reddish brown, spotted and marked with a darker hue. The tail of the female is short. The statement is made, however, that some hens kept for six years by Lady Essex gradually assumed an attire like that of the males.

Fly-fishers highly esteem the crest and feathers on the back of the neck of the male, as many of the artificial baits owe their chief beauty to the Golden Pheasant.

According to Latham, it is called by the Chinese Keuki, or Keukee, a word which means gold flower fowl.

“A merry welcome to thee, glittering bird!

Lover of summer flowers and sunny things!

A night hath passed since my young buds have heard

The music of thy rainbow-colored wings—

Wings that flash spangles out where’er they quiver,

Like sunlight rushing o’er a river.”

golden pheasant.

golden pheasant.

THE NONPAREIL.

O full of fight is this little bird, that the bird trappers take advantage of his disposition to make him a prisoner. They place a decoy bird on a cage trap in the attitude of defense, and when it is discovered by the bird an attack at once follows, and the fighter soon finds himself caught.

They are a great favorite for the cage, being preferred by many to the Canary. Whatever he may lack as a songster he more than makes up by his wonderful beauty. These birds are very easily tamed, the female, even in the wild state, being so gentle that she allows herself to be lifted from the nest. They are also called the Painted Finch or Painted Bunting. They are found in our Southern States and Mexico. They are very numerous in the State of Louisiana and especially about the City of New Orleans, where they are greatly admired by the French inhabitants, who, true to their native instincts, admire anything with gay colors. As the first name indicates, he has no equal, perhaps, among the songsters for beauty of dress. On account of this purple hood, he is called by the French Le Pape, meaning The Pope.

The bird makes its appearance in the Southern States the last of April and, during the breeding season, which lasts until July, two broods are raised. The nests are made of fine grass and rest in the crotches of twigs of the low bushes and hedges. The eggs have a dull or pearly-white ground and are marked with blotches and dots of purplish and reddish brown.

It is very pleasing to watch the numerous changes which the feathers undergo before the male bird attains his full beauty of color. The young birds of both sexes during the first season are of a fine olive green color on the upper parts and a pale yellow below. The female undergoes no material change in color except becoming darker as she grows older. The male, on the contrary, is three seasons in obtaining his full variety of colors. In the second season the blue begins to show on his head and the red also makes its appearance in spots on the breast. The third year he attains his full beauty.

Their favorite resorts are small thickets of low trees and bushes, and when singing they select the highest branches of the bush. They are passionately fond of flies and insects and also eat seeds and rice.

Thousands of these birds are trapped for the cage, and sold annually to our northern people and also in Europe. They are comparatively cheap, even in our northern bird markets, as most of them are exchanged for our Canaries and imported birds that cannot be sent directly to the south on account of climatic conditions.

Many a northern lady, while visiting the orange groves of Florida, becomes enchanted with the Nonpareil in his wild state, and some shrewd and wily negro, hearing her expressions of delight, easily procures one, and disposes of it to her at an extravagant price.

THE AUSTRALIAN GRASS PARRAKEET.

I am a Parrakeet. I belong to the Parrot family. A man bought me and brought me here.

It is not warm here, as it was where I came from. I almost froze coming over here.

I am not kept in a cage. I stay in the house and go about as I please.

There is a Pussy Cat in the house. Sometimes I ride on her back. I like that.

I used to live in the grass lands. It was very warm there. I ran among the thick grass blades, and sat on the stems and ate seeds.

I had a wife then. Her feathers were almost like mine. We never made nests. When we wanted a nest, we found a hole in a gum tree. I used to sing to my wife while she sat on the nest.

I can mock other birds. Sometimes I warble and chirp at the same time. Then it sounds like two birds singing. My tongue is short and thick, and this helps me to talk. But I have been talking too much. My tongue is getting tired.

I think I’ll have a ride on Pussy’s back. Good bye.

ARRAKEETS have a great fondness for the grass lands, where they may be seen in great numbers, running amid the thick grass blades, clinging to their stems, or feeding on their seeds.

Grass seed is their constant food in their native country. In captivity they take well to canary seed, and what is remarkable, never pick food with their feet, as do other species of parrots, but always use their beaks. “They do not build a nest, but must be given a piece of wood with a rough hole in the middle, which they will fill to their liking, rejecting all soft lining of wool or cotton that you may furnish them.”

Only the male sings, warbling nearly all day long, pushing his beak at times into his mate’s ear as though to give her the full benefit of his song. The lady, however, does not seem to appreciate his efforts, but generally pecks him sharply in return.

A gentleman who brought a Parrakeet from Australia to England, says it suffered greatly from the cold and change of climate and was kept alive by a kind-hearted weather-beaten sailor, who kept it warm and comfortable in his bosom. It was not kept in a cage, but roamed at will about the room, enjoying greatly at times, a ride on the cat’s back. At meals he perched upon his master’s shoulder, picking the bits he liked from a plate set before him. If the weather was cold or chilly, he would pull himself up by his master’s whiskers and warm his feet by standing on his bald head. He always announced his master’s coming by a shrill call, and no matter what the hour of night, never failed to utter a note of welcome, although apparently asleep with his head tucked under his wing.

australian grass parrakeet.

australian grass parrakeet.

cock-of-the-rock.

cock-of-the-rock.

THE COCK-OF-THE-ROCK.

HE Cock-of-the-Rock lives in Guiana. Its nest is found among the rocks. T. K. Salmon says: “I once went to see the breeding place of the Cock-of-the-Rock; and a darker or wilder place I have never been in. Following up a mountain stream the gorge became gradually more enclosed and more rocky, till I arrived at the mouth of a cave with high rock on each side, and overshadowed by high trees, into which the sun never penetrated. All was wet and dark, and the only sound heard was the rushing of the water over the rocks. We had hardly become accustomed to the gloom when a nest was found, a dark bird stealing away from what seemed to be a lump of mud upon the face of the rock. This was a nest of the Cock-of-the-Rock, containing two eggs; it was built upon a projecting piece, the body being made of mud or clay, then a few sticks, and on the top lined with green moss. It was about five feet from the water. I did not see the male bird, and, indeed, I have rarely ever seen the male and female birds together, though I have seen both sexes in separate flocks.”

The eggs are described as pale buff with various sized spots of shades from red-brown to pale lilac.

It is a solitary and wary bird, feeding before sunrise and after sunset and hiding through the day in sombre ravines.

Robert Schomburgh describes its dance as follows:

“While traversing the mountains of Western Guiana we fell in with a pack of these splendid birds, which gave me the opportunity of being an eye witness of their dancing, an accomplishment which I had hitherto regarded as a fable. We cautiously approached their ballet ground and place of meeting, which lay some little distance from the road. The stage, if we may so call it, measured from four to five feet in diameter; every blade of grass had been removed and the ground was as smooth as if leveled by human hands. On this space we saw one of the birds dance and jump about, while the others evidently played the part of admiring spectators. At one moment it expanded its wings, threw its head in the air, or spread out its tail like a peacock scratching the ground with its foot; all this took place with a sort of hopping gait, until tired, when on emitting a peculiar note, its place was immediately filled by another performer. In this manner the different birds went through their terpsichorean exercises, each retiring to its place among the spectators, who had settled on the low bushes near the theatre of operations. We counted ten males and two females in the flock. The noise of a breaking stick unfortunately raised an alarm, when the whole company of dancers immediately flew off.”

“The Indians, who place great value on their skins, eagerly seek out their playing grounds, and armed with their blow-tubes and poisoned arrows, lie in wait for the dances. The hunter does not attempt to use his weapon until the company is quite engrossed in the performance, when the birds become so preoccupied with their amusement that four or five are often killed before the survivors detect the danger and decamp.”

THE RED BIRD OF PARADISE.

My home is on an island where it is very warm. I fly among the tall trees and eat fruit and insects.

See my beautiful feathers. The ladies like to wear them in their hats.

The feathers of my wife are brown, but she has no long tail feathers.

My wife thinks my plumes are very beautiful.

When we have a party, we go with our wives to a tall tree. We spread our beautiful plumes while our wives sit and watch us.

Sometimes a man finds our tree and builds a hut among the lower branches.

He hides in the hut and while we are spreading our feathers shoots at us.

The arrows are not sharp. They do not draw blood.

When they dry the skins they take off the feet and wings. This is why people used to think we had neither feet nor wings.

They also thought we lived on the dews of heaven and the honey of flowers. This is why we are called the Birds of Paradise.

“Upon its waving feathers poised in air,

Feathers, or rather clouds of golden down,

With streamers thrown luxuriantly out

In all the wantonness of winged wealth.”

red bird of paradise.

red bird of paradise.

THE RED BIRD OF PARADISE.

IRDS of Paradise are found only in New Guinea and on the neighboring islands. The species presented here is found only on a few islands.

In former days very singular ideas prevailed concerning these birds and the most extravagant tales were told of the life they led in their native lands. The natives of New Guinea, in preparing their skins for exportation, had removed all traces of legs, so that it was popularly supposed they possessed none, and on account of their want of feet and their great beauty, were called the Birds of Paradise, retaining, it was thought, the forms they had borne in the Garden of Eden, living upon dew or ether, through which it was imagined they perpetually floated by the aid of their long cloud-like plumage.

Of one in confinement Dr. Bennett says: “I observed the bird, before eating a grasshopper, place the insect upon the perch, keep it firmly fixed by the claws, and, divesting it of the legs, wings, etc., devour it with the head always first. It rarely alights upon the ground, and so proud is the creature of its elegant dress that it never permits a soil to remain upon it, frequently spreading out its wings and feathers, regarding its splendid self in every direction.”

The sounds uttered by this bird are very peculiar, resembling somewhat the cawing of the Raven, but change gradually to a varied scale in musical gradations, like he, hi, ho, how! He frequently raises his voice, sending forth notes of such power as to be heard at a long distance. These notes are whack, whack, uttered in a barking tone, the last being a low note in conclusion.

While creeping amongst the branches in search of insects, he utters a soft clucking note. During the entire day he flies incessantly from one tree to another, perching but a few moments, and concealing himself among the foliage at the least suspicion of danger.

In Bennett’s “Wanderings” is an entertaining description of Mr. Beale’s bird at Maceo. “This elegant bird,” he says, “has a light, playful, and graceful manner, with an arch and impudent look, dances about when a visitor approaches the cage, and seems delighted at being made an object of admiration. It bathes twice daily, and after performing its ablutions throws its delicate feathers up nearly over its head, the quills of which have a peculiar structure, enabling the bird to effect this object. To watch this bird make its toilet is one of the most interesting sights of nature; the vanity which inspires its every movement, the rapturous delight with which it views its enchanting self, its arch look when demanding the spectator’s admiration, are all pardonable in a delicate creature so richly embellished, so neat and cleanly, so fastidious in its tastes, so scrupulously exact in its observances, and so winning in all its ways.”

Says a traveler in New Guinea: “As we were drawing near a small grove of teak-trees, our eyes were dazzled with a sight more beautiful than any I had yet beheld. It was that of a Bird of Paradise moving through the bright light of the morning sun. I now saw that the birds must be seen alive in their native forests, in order to fully comprehend the poetic beauty of the words Birds of Paradise. They seem the inhabitants of a fairer world than ours, things that have wandered in some way from their home, and found the earth to show us something of the beauty of worlds beyond.”

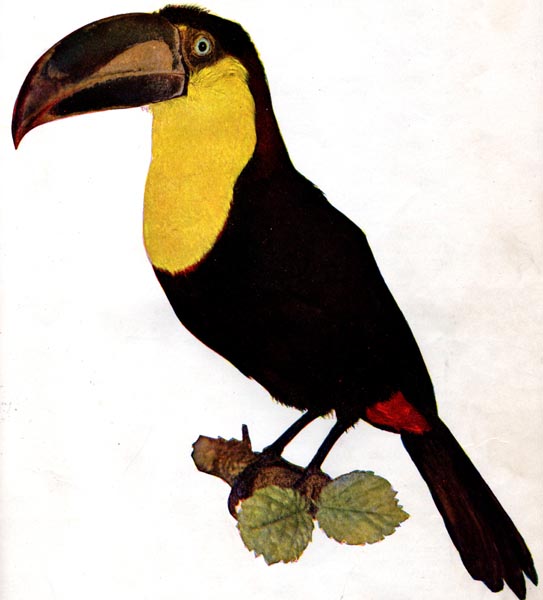

THE YELLOW THROATED TOUCAN.

I am a Toucan and I live in a very warm country.

See my handsome black coat and my yellow vest.

My toes are like a parrot’s, two in front and two behind.

They help me to hold to the limbs.

Look at my large beak. It looks heavy but it is not, as it is filled with air cells. These make it very light. Do you like my blue eyes?

My nest is very hard to find. If I tell you where it is, you will not take the eggs, will you? It is in a hollow limb of a very high tree.

I am very fond of fruit, and for this reason the people on the plantations do not like me very well.

I can fly very fast, but I cannot get along so well on the ground. I keep my feet far apart and hop.

I like to sit in the top of the tallest trees. Then I am not afraid. Nothing can reach me there but a rifle ball.

I do not like the owl, he is so ugly. When we find an owl we get in a circle around him and snap our great beaks, and jerk our tails up and down and scream. He is very much afraid of us.

The people where I live like our yellow breasts. They wear them on their heads, and also put them on the ends of their bows.

We sometimes sit together in a tree and snap our beaks and shout. This is why we have been called “Preacher Birds.”

We can scream so loud that we may be heard a mile away. Our song is “Tucano! Tucano!”

I think it is a pretty song, but the people do not like it very much.

yellow throated toucan.

yellow throated toucan.

THE YELLOW THROATED TOUCAN.

HE Toucans are a numerous race of South American birds, at once recognizable by the prodigious size of their beaks and by the richness of their plumage. “These birds are very common,” says Prince Von Wied, “in all parts of the extensive forests of the Brazils and are killed for the table in large numbers during the cool seasons. Their eggs are deposited in the hollow limbs and holes of the colossal trees, so common in the tropical forests, but their nests are very difficult to find. The egg is said to be white. They are very fond of fruit, oranges, guavas and plantains, and when these fruits are ripe make sad havoc among the neighboring plantations. In return for these depredations the planter eats their flesh, which is very delicate.”

The flight of these birds is easy and graceful, sweeping with facility over the loftiest trees of their native forests, their strangely developed bills being no encumbrance to them, replete as they are with a tissue of air-filled cells rendering them very light and even buoyant.

On the ground they get along with a rather awkward hopping movement, their legs being kept widely apart. In ascending a tree they do not climb but mount from one branch to another with a series of jumps, ascending to the tops of the very loftiest trees, safe from every missile except a rifle ball. They have a habit of sitting on the branches in flocks, lifting their bills, clattering them together, and shouting hoarsely all the while, from which custom the natives call them Preacher-birds. Sometimes the whole party, including the sentinel, set up a simultaneous yell so deafeningly loud that it can be heard a mile. They are very loquacious birds and are often discovered through their perpetual chattering. Their cry resembles the word “Tucano,” which has given origin to the peculiar name.

When settling itself to sleep, the Toucan packs itself up in a very systematic manner, supporting its huge beak by resting it on its back, and tucking it completely among the feathers, while it doubles its tail across its back just as if it moved on hinges. So completely is the large bill hidden among the feathers, that hardly a trace of it is visible in spite of its great size and bright color, so that the bird when sleeping looks like a great ball of loose feathers.

Sir R. Owen concludes that the large beak is of service in masticating food compensating for the absence of any grinding structures in the intestinal tract.

Says a naturalist: “We turned into a gloomy forest and for some time saw nothing but a huge brown moth, which looked almost like a bat on the wing. Suddenly we heard high upon the trees a short shrieking sort of noise ending in a hiss, and our guide became excited and said, “Toucan!” The birds were very wary and made off. They are much in quest and often shot at. At last we caught sight of a pair, but they were at the top of such a high tree that they were out of range. Presently, when I had about lost hope, I heard loud calls, and three birds came and settled in a low bush in the middle of the path. I shot one and it proved to be a very large toucan. The bird was not quite dead when I picked it up, and it bit me severely with its huge bill.”

THE RED-RUMPED TANAGER.

I have just been singing my morning song, and I wish you could have heard it. I think you would have liked it.

I always sing very early in the morning. I sing because I am happy, and the people like to hear me.

My home is near a small stream, where there are low woods and underbrush along its banks.

There is an old dead tree there, and just before the sun is up I fly to this tree.

I sit on one of the branches and sing for about half an hour. Then I fly away to get my breakfast.

I am very fond of fruit. Bananas grow where I live, and I like them best of all.

I eat insects, and sometimes I fly to the rice fields and swing on the stalks and eat rice.

The people say I do much harm to the rice, but I do not see why it is wrong for me to eat it, for I think there is enough for all.

I must go now and get my breakfast. If you ever come to see me I will sing to you.

I will show you my wife, too. She looks just like me. Be sure to get up very early. If you do not, you will be too late for my song.

“Birds, Birds! ye are beautiful things,

With your earth-treading feet and your cloud-cleaving wings.

Where shall man wander, and where shall he dwell—

Beautiful birds—that ye come not as well?

Ye have nests on the mountain, all rugged and stark,

Ye have nests in the forest, all tangled and dark;

Ye build and ye brood ‘neath the cottagers’ eaves,

And ye sleep on the sod, ’mid the bonnie green leaves;

Ye hide in the heather, ye lurk in the brake,

Ye dine in the sweet flags that shadow the lake;

Ye skim where the stream parts the orchard decked land,

Ye dance where the foam sweeps the desolate strand.”

red-rumped tanager.

red-rumped tanager.

THE RED-RUMPED TANAGER.

N American family, the Tanagers are mostly birds of very brilliant plumage. There are 300 species, a few being tropical birds. They are found in British and French Guiana, living in the latter country in open spots of dwellings and feeding on bananas and other fruits. They are also said to do much harm in the rice fields.

In “The Auk,” of July, 1893, Mr. George K. Cherrie, of the Field Museum, says of the Red-Rumped Tanager:

“During my stay at Boruca and Palmar, (the last of February) the breeding season was at its height, and I observed many of the Costa Rica Red-Rumps nesting. In almost every instance where possible I collected both parents of the nests, and in the majority of cases found the males wearing the same dress as the females. In a few instances the male was in mottled plumage, evidently just assuming the adult phase, and in a lesser number of examples the male was in fully adult plumage—velvety black and crimson red. From the above it is clear that the males begin to breed before they attain fully adult plumage, and that they retain the dress of the female until, at least, the beginning of the second year.

“While on this trip I had many proofs that, in spite of its rich plumage, and being a bird of the tropics, it is well worthy to hold a place of honor among the song birds. And if the bird chooses an early hour and a secluded spot for expressing its happiness, the melody is none the less delightful. At the little village of Buenos Aires, on the Rio Grande of Terraba, I heard the song more frequently than at any other point. Close by the ranch house at which we were staying, there is a small stream bordered by low woods and underbrush, that formed a favorite resort for the birds. Just below the ranch is a convenient spot where we took our morning bath. I was always there just as the day was breaking. On the opposite bank was a small open space in the brush occupied by the limbs of a dead tree. On one of these branches, and always the same one, was the spot chosen by a Red-rump to pour forth his morning song. Some mornings I found him busy with his music when I arrived, and again he would be a few minutes behind me. Sometimes he would come from one direction, sometimes from another, but he always alighted at the same spot and then lost no time in commencing his song. While singing, the body was swayed to and fro, much after the manner of a canary while singing. The song would last for perhaps half an hour, and then away the singer would go. I have not enough musical ability to describe the song, but will say that often I remained standing quietly for a long time, only that I might listen to the music.”

THE GOLDEN ORIOLE.

E find the Golden Oriole in America only. According to Mr. Nuttall, it is migratory, appearing in considerable numbers in West Florida about the middle of March. It is a good songster, and in a state of captivity imitates various tunes.

This beautiful bird feeds on fruits and insects, and its nest is constructed of blades of grass, wool, hair, fine strings, and various vegetable fibers, which are so curiously interwoven as to confine and sustain each other. The nest is usually suspended from a forked and slender branch, in shape like a deep basin and generally lined with fine feathers.

“On arriving at their breeding locality they appear full of life and activity, darting incessantly through the lofty branches of the tallest trees, appearing and vanishing restlessly, flashing at intervals into sight from amidst the tender waving foliage, and seem like living gems intended to decorate the verdant garments of the fresh clad forest.”

It is said these birds are so attached to their young that the female has been taken and conveyed on her eggs, upon which with resolute and fatal instinct she remained faithfully sitting until she expired.

An Indiana gentleman relates the following story:

“When I was a boy living in the hilly country of Southern Indiana, I remember very vividly the nesting of a pair of fine Orioles. There stood in the barn yard a large and tall sugar tree with limbs within six or eight feet of the ground.

“At about thirty feet above the ground I discovered evidences of an Oriole’s nest. A few days later I noticed they had done considerably more work, and that they were using horse hair, wool and fine strings. This second visit seemed to create consternation in the minds of the birds, who made a great deal of noise, apparently trying to frighten me away. I went to the barn and got a bunch of horse hair and some wool, and hung it on limbs near the nest. Then climbing up higher, I concealed myself where I could watch the work. In less than five minutes they were using the materials and chatted with evident pleasure over the abundant supply at hand.

“They appeared to have some knowledge of spinning, as they would take a horse hair and seemingly wrap it with wool before placing it in position on the nest.

“I visited these birds almost daily, and shortly after the nest was completed I noticed five little speckled eggs in it. The female was so attached to the nest that I often rubbed her on the back and even lifted her to look at the eggs.”

golden oriole.

golden oriole.TESTIMONIALS.

Chicago, December 10th, 1896.

Nature Study Publishing Company.

Dear Sirs: I am very much pleased with this movement to give such substantial and tangible aid to us on this subject, and for your kind offer also.

Respectfully,

Harriet N. Winchell,

Principal Tilden School.

St. Joseph, Mich., January 4, 1897.

Principal W. J. Black,

Chicago.

Dear Sir: Thanks for sample copy of “Birds.” It is by far the finest thing I have ever seen in that line. I shall take great pleasure in presenting it to my teachers, and shall be glad to be of any assistance to you that I am able.

Yours,

George W. Loomis,

Superintendent City Schools.

Des Moines, Iowa, January 5, 1897.

Nature Study Publishing Company,

Fisher Building, Chicago.

I have just seen the January number of “Birds,” illustrated by color photography; and think it instructive, delightful and beautiful.

Very sincerely,

Mrs. Minnie Theresa Hatch,

Principal Washington School.

Luther, Mich., December 31st, 1896.

W. E. Watt,

Chicago, Ill.

Dear Sir: Your serial on Birds received and after examination I have no hesitation in saying that it is the best publication of the kind that I have ever seen and I will do all that I can for you in presenting it to my teachers and recommending it to their favorable notice.

Very truly,

E. G. Johnson,

Commissioner of Schools.